- A full labor-market recovery is more than a year away, but the rebound is still fast by historical standards.

- The pandemic saw unprecedented job loss, but payrolls are bouncing back faster than in past downturns.

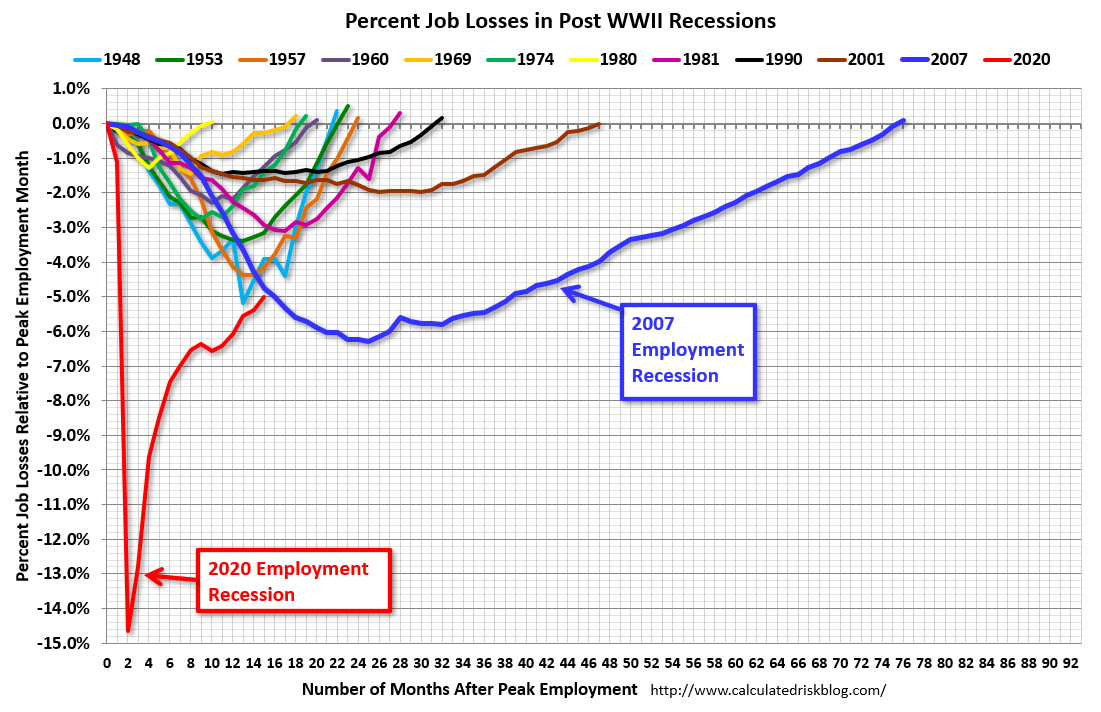

- The US is on track to recoup all lost jobs in two years. The same feat took more than six years after the Great Recession.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

The US labor market is far from a full rebound. Compared to the last recession, however, the recovery is moving at a breakneck pace.

The economy added 559,000 nonfarm payrolls in May, data out Friday showed. The reading marked a fifth consecutive month of job additions and a strong uptick from the disappointing gains seen in April. The US unemployment rate also hit a pandemic low of 5.8% and major stock indices neared record highs on the encouraging news.

Still, payroll growth hasn't enjoyed the kind of V-shaped bounce-back staged elsewhere in the economy. At May's pace of job creation, it would still take until July 2022 for the economy to recoup every job lost during the pandemic. It would take about another year from then to recapture jobs that would've been made had the pandemic not occurred. The projections also don't take the nationwide labor shortage into account, which could further drag on job additions.

Bill McBride/Calculated Risk

Comparing the pandemic recovery to the Great Recession and other downturns tells an entirely different story. In a Friday post, economics blogger Bill McBride of Calculated Risk contrasted job creation from recent months to that seen during post-World War II recessions.

The trend is clear: despite seeing far more severe job losses at the start of the recession, the labor market's recovery is the most V-shaped in modern history.

A few factors explain the pronounced rebound. The government's response throughout the pandemic was unprecedented. Congress approved roughly $5 trillion in fiscal stimulus, and the Federal Reserve eased monetary conditions through historically low rates, massive asset-purchase programs, and extraordinary lending programs. Combined, the efforts helped economic activity bounce back relatively soon after the pandemic first hit.

The nature of the recession also played a role. The economic crisis was simply a symptom of a once-in-a-century pandemic. Lockdown measures used to curb the virus's spread were a top reason for weaker activity. Once those restrictions were lifted, Americans with pent-up demand and bolstered savings got out and revived the economy.

The current downturn also doesn't possess the same structural problems faced in the late 2000s. The Great Recession was fueled by a collapse of integral financial systems. Long-trusted institutions were suddenly behind an economic collapse, and the government was forced to step in with then-unheard-of support. Distrust in said institutions and severe damage throughout the housing market led to a painful and plodding recovery.

The COVID-19 crisis, by comparison, was simple. A deadly virus was spreading throughout the country, so authorities forced lockdowns that caused great harm to the economy.

The US has also learned from the Great Recession and the recovery that followed. An early push for fiscal austerity and inadequate aid for state and local governments hindered the labor market's healing for years after the financial crisis. Payrolls didn't return to their pre-recession highs until more than six years after the initial drop, longer than any previous postwar recession.

Policymakers are trying something else this time around. The $1.9 trillion stimulus measure approved in March included $350 billion for state, city, and local governments to offset budget shortfalls. On the monetary front, the Fed's newly updated goals signal it will maintain ultra-easy monetary conditions well after the pandemic threat fades.

"Now is not the time to be talking about an exit," Fed Chair Jerome Powell said in January. "I think that is another lesson of the global financial crisis, 'be careful not to exit too early.'"